First a little bit about the "name" of this manuscript. If you are already familiar with how shelfmarks work, you can skip to the next paragraph. Many manuscripts are famous and have names that are well known outside of the realm of medievalists, the Book of Kells for example. Others are more obscure, but are well known to medievalists, the Quedlinburg Itala or the Vatican Virgil, for example. Others may have names that uniquely identify them, but are not well known to anyone other than a specialist. Most manuscripts don't have names, though, and are identified only by shelfmarks. Shelfmarks are the cataloging labels given to each manuscript by the institution that holds it. Each institution makes its own rules as to how to assign shelfmarks. Some just number them; MS 1, MS 2, etc. Others will sort by their manuscripts into collections, and number each collection. The collections may be sorted by language, or manuscript type, or by donor. Some large institutions might have several different types of collections. In any case, the full shelfmark will identify a manuscript precisely. (Some institutions that only hold a few manuscripts, or perhaps only one, don't use shelfmarks at all.) These shelfmarks are a kind of secret passwords for medievalists. You stand a much better chance of getting an institution to let you look at a manuscript if you know its shelfmark. Some institutions, rather than simply numbering the manuscript, use a more complicated scheme, that gives you the precise location of the manuscript. To do this you must identify the bookcase a manuscript is in, the shelf of the bookcase, and the position of the manuscript on the shelf. This is what Durham Cathedral does. This manuscript is A II 10. This translates to the first bookcase (A), the second shelf (II), and the tenth manuscript (10).

First a little bit about the "name" of this manuscript. If you are already familiar with how shelfmarks work, you can skip to the next paragraph. Many manuscripts are famous and have names that are well known outside of the realm of medievalists, the Book of Kells for example. Others are more obscure, but are well known to medievalists, the Quedlinburg Itala or the Vatican Virgil, for example. Others may have names that uniquely identify them, but are not well known to anyone other than a specialist. Most manuscripts don't have names, though, and are identified only by shelfmarks. Shelfmarks are the cataloging labels given to each manuscript by the institution that holds it. Each institution makes its own rules as to how to assign shelfmarks. Some just number them; MS 1, MS 2, etc. Others will sort by their manuscripts into collections, and number each collection. The collections may be sorted by language, or manuscript type, or by donor. Some large institutions might have several different types of collections. In any case, the full shelfmark will identify a manuscript precisely. (Some institutions that only hold a few manuscripts, or perhaps only one, don't use shelfmarks at all.) These shelfmarks are a kind of secret passwords for medievalists. You stand a much better chance of getting an institution to let you look at a manuscript if you know its shelfmark. Some institutions, rather than simply numbering the manuscript, use a more complicated scheme, that gives you the precise location of the manuscript. To do this you must identify the bookcase a manuscript is in, the shelf of the bookcase, and the position of the manuscript on the shelf. This is what Durham Cathedral does. This manuscript is A II 10. This translates to the first bookcase (A), the second shelf (II), and the tenth manuscript (10).This manuscript is a fragment of an early Insular gospel book. It is usually known only by the its shelfmark because there are at least two other fragmentary Insular gospel books at Durham Cathedral (MSS A II 16, and A II 17). MS A II 17 is sometimes called the "Durham Gospels". Kirsten Ataoguz at Early Medieval Art calls this the "Earlier Durham Gospels" and A II 17 the later Durham Gospels.

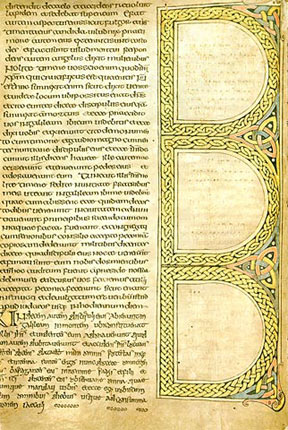

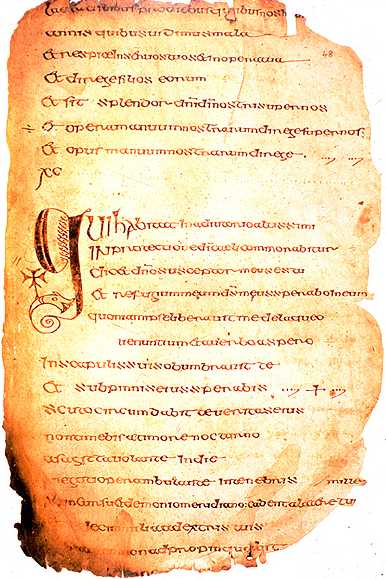

This manuscript is earliest in a sequence of magnificently decorated gospel books that stretches to the Book of Kells and beyond. This manuscript dates to the early 7th century and is not much younger than the Cathach of St. Columba. The surviving fragments contain two important pieces of decoration, on facing pages. Folio 3v* (see illustration above) contains the end of the the Gospel of Matthew. The text is in the left hand column, the other column contains a frame shaped like three capital letter "Ds" stacked one on top of the other. Each frame is decorated with a knot work pattern, and each frame has a different pattern. (Dr. Ataoguz suggests having students describe these patterns as an exercise in observation and description. Other than noting that the lower 'D' is decorated with a traditional three strand braid, I would find this very difficult.) The triangular spaces between, above and below the "D" frames are filled with larger, looser triangular knots. Inside the frames are written the explicit** to Matthew, the incipit** to the Gospel of Mark, and the Pater Noster, or Lord's Prayer, in Greek, but written in Latin letters. Facing this page is the opening page to the Gospel of Mark. (see illustration at right.) It starts with a large decorated initial. This initial takes the first three letters of the the opening word "Initium" and fuses them into a large monogram. The monogram is shorter on the right side than it is on the left. Each subsequent letter in the opening word is smaller than the preceding letter. This diminuation of letters was first seen in the Cathach. A manuscript of Jerome at Bobbio from the early 7th century also contains an "INI" monogram that is very similar in form to this monogram (see illustration below). This would suggest a fairly wide spread artistic convention.

This manuscript is earliest in a sequence of magnificently decorated gospel books that stretches to the Book of Kells and beyond. This manuscript dates to the early 7th century and is not much younger than the Cathach of St. Columba. The surviving fragments contain two important pieces of decoration, on facing pages. Folio 3v* (see illustration above) contains the end of the the Gospel of Matthew. The text is in the left hand column, the other column contains a frame shaped like three capital letter "Ds" stacked one on top of the other. Each frame is decorated with a knot work pattern, and each frame has a different pattern. (Dr. Ataoguz suggests having students describe these patterns as an exercise in observation and description. Other than noting that the lower 'D' is decorated with a traditional three strand braid, I would find this very difficult.) The triangular spaces between, above and below the "D" frames are filled with larger, looser triangular knots. Inside the frames are written the explicit** to Matthew, the incipit** to the Gospel of Mark, and the Pater Noster, or Lord's Prayer, in Greek, but written in Latin letters. Facing this page is the opening page to the Gospel of Mark. (see illustration at right.) It starts with a large decorated initial. This initial takes the first three letters of the the opening word "Initium" and fuses them into a large monogram. The monogram is shorter on the right side than it is on the left. Each subsequent letter in the opening word is smaller than the preceding letter. This diminuation of letters was first seen in the Cathach. A manuscript of Jerome at Bobbio from the early 7th century also contains an "INI" monogram that is very similar in form to this monogram (see illustration below). This would suggest a fairly wide spread artistic convention.This manuscript, fragmentary as it is, is still quite important. It is has the first surviving appearance of the knotwork that would a major motif in later Insular manuscripts. The later Insular gospel books would all use monograms similar to the "INI" monogram used here. It shows the continuation of the strong tradition of the diminuation of letters after an enlarged intitial.

The Bobbio Jerome initial. My apologies for the low quality of the image.

* Most manuscripts were not paginated as modern books are. In modern books, each side of a single leaf is given a new page number. Manuscripts are usually foliated, where each leaf is give a number. The two sides are then termed the "recto" and the "verso". The recto is the "front" side, that is the side that is on the right side of the book when it is opened. The other side, the verso is on the left side of the open book. Individual sides of folios are indicated by giving the folio number and an "r" or "v" for recto or verso.

**The incipit and explicit are the terms for text introducing announcing the beginning (incipit) and end (explicit) of a text. An incipit may read something like, "Here begins the Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ according to Saint Matthew". For the most part, except for an occasional "The End" at the end of some novels, this practice has died out in modern books.

This is a page from the Escorial Beatus (Escorial, Biblioteca Monasterio, Cod. & II. 5). Beatus of Liébana was an 8th century monk who wrote a commentary on the Book of Revelation. Actually "wrote" is a bit of strong word, as what he actually did was compile a bunch of other writer's comments together. For some reason his Commentary became a very popular book in the 9th and 10th centuries. There are twenty some copies extant, most of which are lavishly illustrated, often with full page miniatures. The Beatus manuscripts are an important part of what is called Mozarabic Art. There existed in the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula a tradition of manuscript illustration that was unlike anything else be doing anywhere else in Europe. This tradition emphasized flat, stylized forms for the human bodies. The drapery of the clothes was portrayed as abstract patterns that gave little indication of a body beneath. There was a strong, almost garish sense of color with vivid yellows, greens and reds dominating. The iconography was often startlingly original. It seemed almost as if the entire tradition of book illumination had to be invented anew.

This is a page from the Escorial Beatus (Escorial, Biblioteca Monasterio, Cod. & II. 5). Beatus of Liébana was an 8th century monk who wrote a commentary on the Book of Revelation. Actually "wrote" is a bit of strong word, as what he actually did was compile a bunch of other writer's comments together. For some reason his Commentary became a very popular book in the 9th and 10th centuries. There are twenty some copies extant, most of which are lavishly illustrated, often with full page miniatures. The Beatus manuscripts are an important part of what is called Mozarabic Art. There existed in the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula a tradition of manuscript illustration that was unlike anything else be doing anywhere else in Europe. This tradition emphasized flat, stylized forms for the human bodies. The drapery of the clothes was portrayed as abstract patterns that gave little indication of a body beneath. There was a strong, almost garish sense of color with vivid yellows, greens and reds dominating. The iconography was often startlingly original. It seemed almost as if the entire tradition of book illumination had to be invented anew.